Hitler’s Terrible Tariffs

The Atlantic

04/10/2025

The hitler tariffs, announced on Friday, February 10, 1933, stunned observers. “The dimension of the tariff increases have in fact exceeded all expectations,” the Vossische Zeitung wrote disapprovingly, proclaiming the moment a “fork in the road” for the German economy. It appeared that Europe’s largest and most industrialized nation would suddenly be returning “to the furrow and the plow.” The New York Times saw this for what it was: “a trade war” against its European neighbors.

The primary targets of the Hitler tariffs—the Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands—were outraged by the sudden suspension of favored-nation trading status on virtually all agricultural products, as well as on textiles, with tariffs in some cases rising 500 percent. With its livestock essentially banished from the German market, Denmark, for example, was facing substantial losses. Farmers panicked. The Danes and Swedes threatened “retaliatory measures,” as did the Dutch, who warned the Germans that the countermeasures would be felt as “palpable blows” to German industrial exports. That proved to be true.

“Our exports have shrunk significantly,” Foreign Minister Neurath informed Hitler in one cabinet meeting, “and our relations to our neighboring countries are threatening to deteriorate.” Neurath noted that informal contacts with Dutch interlocutors had been “brusquely broken off.” Trade relations with Sweden and Denmark were similarly strained, as were those with France and Yugoslavia. Finance Minister Krosigk anticipated that the agricultural sector would require an additional 100 million reichsmarks in deficit spending.

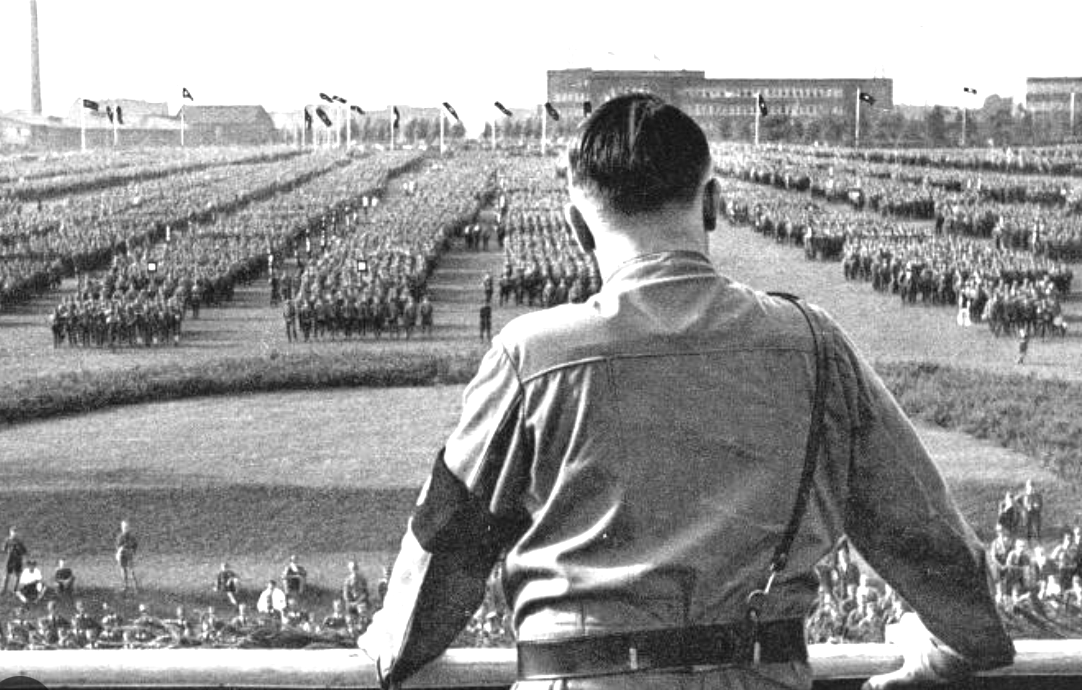

Hitler launched his trade war on the second Friday of his chancellorship. That evening, he appeared in the Berlin Sportpalast, the city’s largest venue, for a rally in front of thousands of jubilant followers. It was his first public appearance as chancellor, and it served as a victory lap. Hitler dispensed with the dark suit he wore in cabinet meetings in favor of his brown storm-trooper uniform with a bright-red swastika armband.

In his address, Hitler declared that the entire country needed to be rebuilt after years of mismanagement by previous governments. He spoke of the “sheer madness” of international obligations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, of the need to restore “life, liberty, and happiness” to the German people, of the need for “cleansing” the bureaucracy, public life, culture, the population, “every aspect of our life.” His tariff regime, he implied, would help restore the pride and honor of German self-reliance.

“Never believe in help from abroad, never on help from outside our own nation, our own people,” Hitler said. “The future of the German people is to be found in our own selves.”

Hitler did not refer specifically to the trade war he had launched that afternoon, just as he did not mention the rearmament plans he had discussed with his cabinet the previous day. “Billions of reichsmarks are needed for rearmament,” Hitler had told his ministers in that meeting. “The future of Germany depends solely and exclusively on the rebuilding of the army.” Hitler’s trade war with his neighbors would prove to be but a prelude to his shooting war with the world.