Content:

An El Niño is Brewing

The Crucial Years

02/16/2026

America’s abandonment of the “endangerment finding” undergirding national climate policy is not the most important thing that happened last week. That decision was an act of gross stupidity, but it was also perfectly predictable given the people making it, and since America’s not doing anything good on climate anyway it won’t have deep immediate effect. (As is often the case, humorist Alexandra Petri had the best response). What will matter more, I think, for America and for policy going forward, is the news that we’re likely to see another El Niño soon; take this as your first warning that not only the temperature but the politics of the planet are likely to change dramatically, and soon.

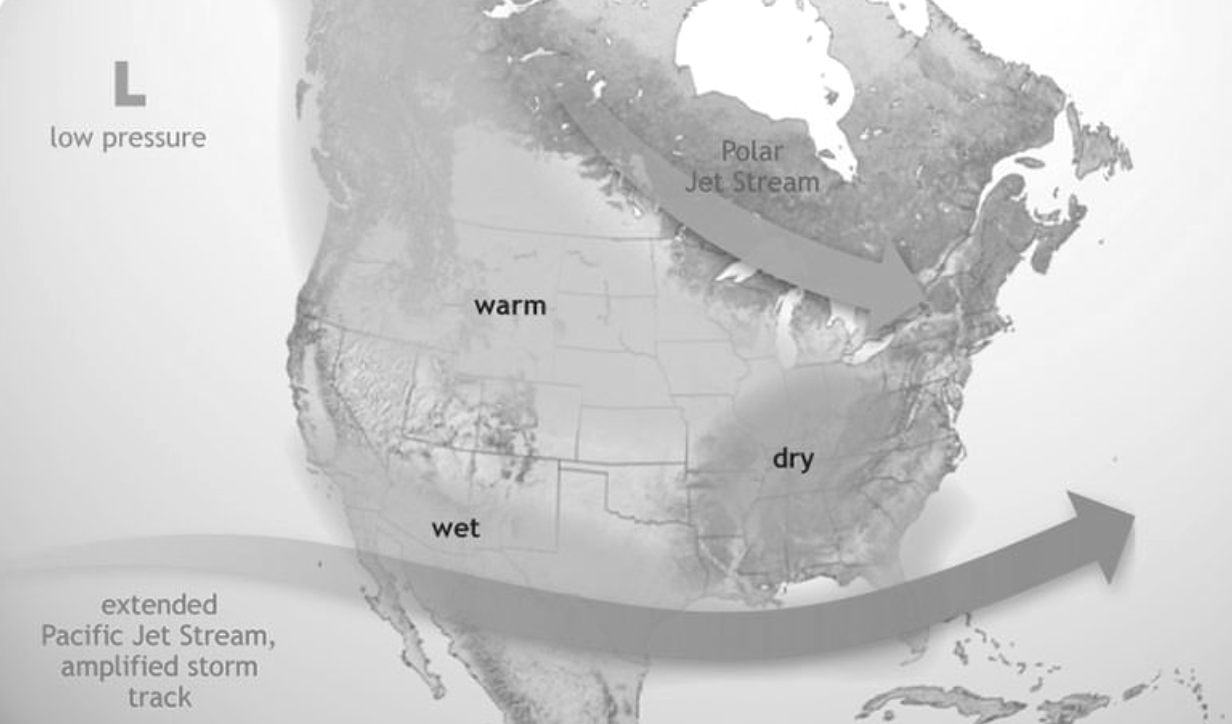

We’re still in a La Niña phase in the Pacific right now—the cooler part of the cycle that meant that 2025’s global temperature was “only” the second or third highest ever, trailing 2023, the last big El Niño year. But that hot phase seems to be returning, and somewhat faster than expected. In the last few weeks, big Kelvin waves have been moving eastward across the Pacific, driving warmer water before them; these can sometimes peter out, but strong westerly wind bursts across the region—counter to the usually dominant trade winds—seem to indicate this one is for real; the best guess of the various forecasters is that sometime between June and September the world will enter an El Niño cycle.

When that happens, prepare for bedlam. Each El Niño event in recent decades has gotten steadily worse, because each one drives the temperature to a new record. That’s because each is super-imposed on a higher baseline temperature that comes with the steady warming of the planet. As James Hansen and his team pointed out in a paper last week, the expected low temperature at the close of the La Niña this spring is expected to be about 1.4 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures, which is higher than the maximum from the last El Niños. We are ever further into the great overheating.

We get fires and floods all the time now, but we get lots more of them when the temperature tilts sharply up. As Eric Niiler reported in the Times, the Pacific warm current “brings the potential for extreme rainfall, powerful storms and drought across some areas of the globe.”