Content:

The Insurrection Act Explained

Brennan Center for Justice

10/07/2025

When can the president invoke the Insurrection Act?

Troops can be deployed under three sections of the Insurrection Act. Each of these sections is designed for a different set of situations. Unfortunately, the law’s requirements are poorly explained and leave virtually everything up to the discretion of the president.

Section 251 allows the president to deploy troops if a state’s legislature (or governor if the legislature is unavailable) requests federal aid to suppress an insurrection in that state. This provision is the oldest part of the law, and the one that has most often been invoked.

While Section 251 requires state consent, Sections 252 and 253 allow the president to deploy troops without a request from the affected state, even against the state’s wishes. Section 252 permits deployment in order to “enforce the laws” of the United States or to “suppress rebellion” whenever “unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion” make it “impracticable” to enforce federal law in that state by the “ordinary course of judicial proceedings.”

Section 253 has two parts. The first allows the president to use the military in a state to suppress “any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy” that “so hinders the execution of the laws” that any portion of the state’s inhabitants are deprived of a constitutional right and state authorities are unable or unwilling to protect that right. Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy relied on this provision to deploy troops to desegregate schools in the South after the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

The second part of Section 253 permits the president to deploy troops to suppress “any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy” in a state that “opposes or obstructs the execution of the laws of the United States or impedes the course of justice under those laws.” This provision is so bafflingly broad that it cannot possibly mean what it says, or else it authorizes the president to use the military against any two people conspiring to break federal law.

Who decides when the conditions for deployment have been met?

Nothing in the text of the Insurrection Act defines “insurrection,” “rebellion,” “domestic violence,” or any of the other key terms used in setting forth the prerequisites for deployment. Absent statutory guidance, the Supreme Court decided early on that this question is for the president alone to decide. In the 1827 case Martin v. Mott, the Court ruled that “the authority to decide whether [an exigency requiring the militia to be called out] has arisen belongs exclusively to the President, and . . . his decision is conclusive upon all other persons.”

However, there are exceptions to the general rule that courts can’t review a president’s decision to deploy. In subsequent cases, the Supreme Court has suggested that courts may step in if the president acts in bad faith, exceeds “a permitted range of honest judgment,” makes an obvious mistake, or acts in a way manifestly unauthorized by law.

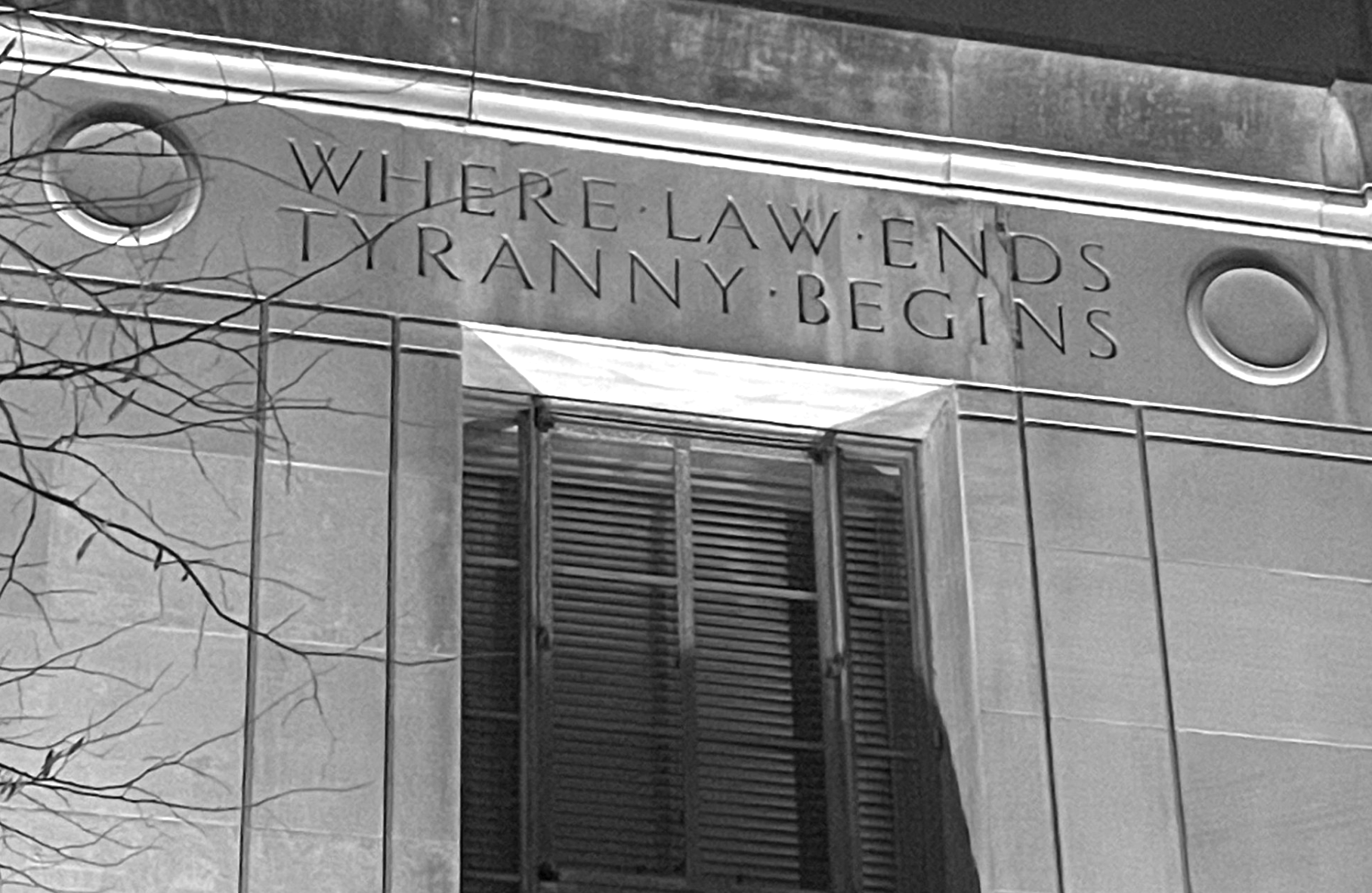

Moreover, even in cases where the courts will not second-guess the decision to deploy troops, the Supreme Court clarified in Sterling v. Constantin (1932) that courts may still review the lawfulness of the military’s actions once deployed. In other words, federal troops are not free to violate other laws or trample on constitutional rights just because the president has invoked the Insurrection Act.

Is invoking the Insurrection Act the same as declaring martial law?

The Insurrection Act does not authorize martial law. The term “martial law” has no established definition, but it is generally understood as a power that allows the military to take over the role of civilian government in an emergency. By contrast, the Insurrection Act generally permits the military to assist civilian authorities (whether state or federal), not take their place. Under current law, the president has no authority to declare martial law.